A Wheelchair-Accessible Web

Even if you are not wheelchair-bound, you may still take notice of the presence (or absence) of accessibility options around you. Last November, I gave a presentation on digital accessibility and inclusion to my colleagues at the town hall. I asked whether they were aware of accessibility options in or around the building. They quickly summarized the ramp next to the stairs at the entrance, the numerous elevators, broader doorways meant for wheelchairs and some even mentioned the hearing loop for hearing aids users in the chamber of the Muncipal Council. We can easily imagine what it takes to be wheelchair-accessible in the physical space, but what does it take to make the online world accessible for everyone?

For those new to the term: digital accessibility refers to the possibility for everyone to use digital tools, online websites and apps, despite a disability. You will find it is quite similar to accessibility in the physical space around you, although up until recently significantly less rules were in place to enforce online accessibility. The EU has been one of the driving forces behind web accessibility. The Web Accessibility Directive (EU2016/2102) has been in force since 2016, which was one of the reasons behind a temporary decree (Tijdelijk besluit digitale toegankelijkheid overheid) issued by the Dutch government in 2018. This temporary decree was permanently written into law by means of the Digital Government Act (Wet digitale overheid) in 2023.

Although the law only came to guarantee the right to web accessibility recently, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) already discussed commitment to “taking appropriate measures to ensure access for persons with disabilities (...) to information and communication technologies and systems”. Digital accessibility is an important human right, as it is a gateway to basic participation in society for people with a disability. And the group of disabled people may be larger than you think.

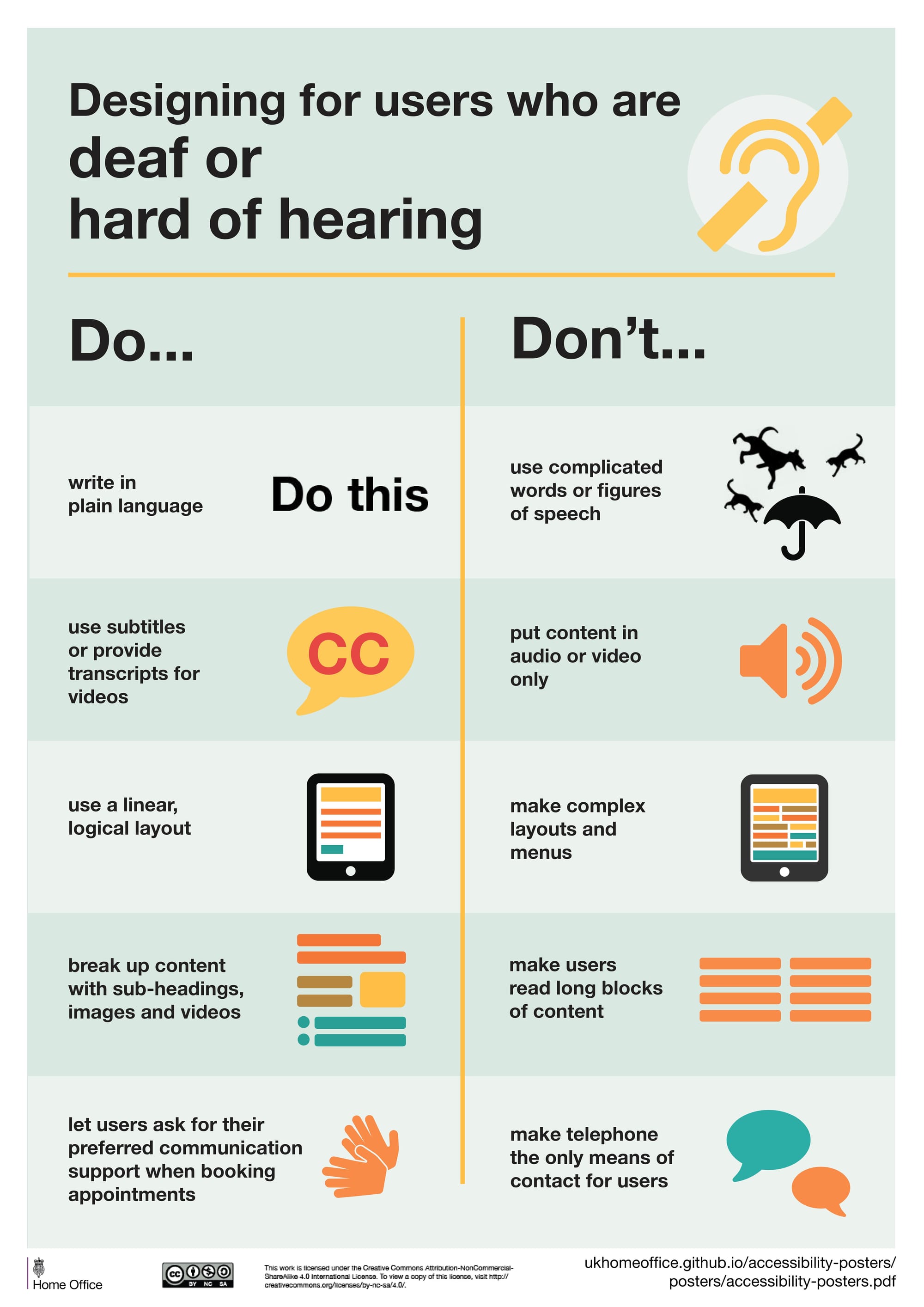

Foundation Accessibility calculates that there are anywhere between 2 and 4.5 million people in the Netherlands with some form of disability. Among them are visually and auditory impaired, people with a mental disability, but also millions of dyslexics, low-literate and elderly people. Up to 25% of Dutch citizens are affected in their use of digital communication with the government. Furthermore, not every disability is permanent, and accessibility may also be useful to the non-disabled in other scenarios as well: think of watching a video without sound but with subtitles on public transport.

Digital Accessibility 101

So, what does the law entail? Well, the general demand is to continuously improve accessibility by ensuring disabled people can access digital resources with the same ease as anyone else. The Ministry of the Interior has, as part of the “Digitoegankelijk” programme, devised a dashboard where you can check the accessibility status of government organizations. To receive a status, an accessibility audit has to be conducted by an independent organization, such as the earlier mentioned Accessibility Foundation, for example. Concretely, your website or app will then be checked based on the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG).

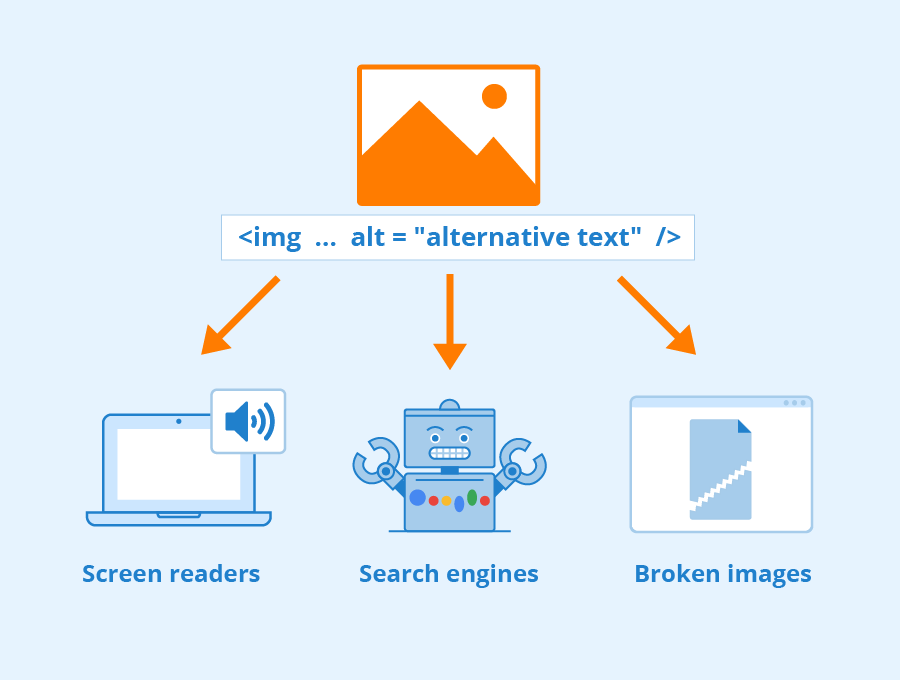

Those guidelines consist of numerous criteria for accessibility, ranging from the presence of alt text for images (for visually impaired users with screenreaders) to the ability to use the software with only a keyboard (for the physically impaired who cannot use a mouse). After the audit you receive a report which can be used to create an accessibility declaration (toegankelijkheidsverklaring), which is obligated by law, even if it states you do not (yet) comply. Based on the declaration, submitted to the Digitoegankelijk dashboard, you receive a status. If you meet all of the WCAG criteria, you are awarded an A status. If you do not meet all of them, but have conducted an Audit, you receive a B status. The C status can be awarded if steps are undertaken to conduct an Audit, but it has not yet been conducted. The A, B and C statuses are all compliant with legal obligations, although that does not mean you are off the hook just yet.

Remember the continuous improvement obligation mentioned earlier? If you are awarded a B or C status, you are compliant, but only temporarily. You will have to keep working towards an A status eventually. Naturally, this takes time and effort and results in costs. Therefore, government organizations may make trade-offs. Additionally, the awarded status is based on an accessibility audit report, but there are many more facets of accessibility that matter.

The many facets of online accessibility

In addition to a website itself, many different forms of content may be published online. These contents should also adhere to accessibility rules. Word documents, PDFs, infographics, audio, video: in the best scenario all of these are accessible to everyone. In many cases, it is very important to ensure correct metadata is embedded in the document. This means that elements such as titles, subheadings, etcetera, should be properly labeled by the creator of the document. If this is not the case, it becomes increasingly hard for screen reader software to properly relay the documents contents. Infographics contain an additional problem: the visual elements are often positionally and thereby also convey meaning to the user. For audio and video, transcripts and subtitles are effective tools, but creating them can be time-consuming, although artificial intelligence is starting to improve this process significantly.

The future and the role of the government

From my experience at the municipality, I believe the challenge of maintaining accessibility amidst the vast volume of government content is widespread. Ensuring new content meets accessibility standards may not necessarily be a problem, but you have to imagine the vast amounts of archived (but still publicly accessible) content the government is maintaining. In a report by the Advisory Board on Public Access and Information Management of last September, the advisory board concludes “the government’s information management is far from in order” and draws particular attention to the sustainable accessibility of digital documents. Not a new feat, because worries about information management date back decades.

Looking ahead, however, the future of online accessibility holds promise, particularly with the increasing technological advancements and the adoption of design principles like “Accessibility by design”. By integrating accessibility considerations into the initial stages of development and content creation, it will be much easier to provide large amounts of content in an accessible way. Additionally, new opportunities created by the advancements in artificial intelligence may also enable us to provide content in an accessible way more rapidly.

The government is certainly not the only one working on accessible design. However, I feel that it is one of the driving forces behind progress made. Recognizing its role in serving the public cause, the government has - in my opinion - a fundamental responsibility to ensure that everyone can participate fully in society, regardless of their physical or cognitive abilities. Leading by example and prioritizing accessibility in its own digital initiatives can be important in setting a precedent for other organizations.

Nonetheless, we must remain realistic: the challenges mentioned earlier may simply mean that it will take some time before we have truly made the digital world as accessible and inclusive as possible for everyone. Even in the physical space, it is not yet always the case that you can get everywhere by wheelchair. Still, I am confident that even digital staircases can give way to a digital ramp.

About Niels

Niels is a UT alumnus and completed a bachelor’s degree in Business Information Technology (‘22) as well as a master’s degree in Communication Science (‘23). His strong interest in politics and public administration and his desire to contribute directly to society in his work made him want to work for the government. He currently works as Advisor Digital Government for the Municipality of Oldenzaal.